Human cloning would still face ethical objections from a majority of concerned people, as well as opposition from diverse religions. Moreover, there remains the limiting consideration asserted earlier: it might be possible to clone a person’s genes, but the individual cannot be cloned.

There are, in mankind, two kinds of heredity: biological and cultural. Cultural inheritance makes possible for humans what no other organism can accomplish: the cumulative transmission of experience from generation to generation. In turn, cultural inheritance leads to cultural evolution, the prevailing mode of human adaptation. For the last few millennia, humans have been adapting the environments to their genes more often than their genes to the environments. Nevertheless, natural selection persists in modern humans, both as differential mortality and as differential fertility, although its intensity may decrease in the future. More than 2,000 human diseases and abnormalities have a genetic causation. Health care and the increasing feasibility of genetic therapy will, although slowly, augment the future incidence of hereditary ailments. Germ-line gene therapy could halt this increase, but at present, it is not technically feasible. The proposal to enhance the human genetic endowment by genetic cloning of eminent individuals is not warranted. Genomes can be cloned; individuals cannot. In the future, therapeutic cloning will bring enhanced possibilities for organ transplantation, nerve cells and tissue healing, and other health benefits.

Chimpanzees are the closest relatives of Homo sapiens, our species. There is a precise correspondence bone by bone between the skeletons of a chimpanzee and a human. Humans bear young like apes and other mammals. Humans have organs and limbs similar to birds, reptiles, and amphibians; these similarities reflect the common evolutionary origin of vertebrates. However, it does not take much reflection to notice the distinct uniqueness of our species. Conspicuous anatomical differences between humans and apes include bipedal gait and an enlarged brain. Much more conspicuous than the anatomical differences are the distinct behaviors and institutions. Humans have symbolic language, elaborate social and political institutions, codes of law, literature and art, ethics, and religion; humans build roads and cities, travel by motorcars, ships, and airplanes, and communicate by means of telephones, computers, and televisions.

Exploring the controversial question: would it be ethical to clone humans for spare parts? This article examines the potential benefits, moral implications, and future consequences of cloning for medical purposes

The cloning of animals has been occurring for a number of years now, and this has now opened up the possibility of cloning humans too. Although there are clear benefits to humankind of cloning to provide spare body parts, I believe it raises a number of worrying ethical issues.

Due to breakthroughs in medical science and improved diets, people are living much longer than in the past. This, though, has brought with it problems. As people age, their organs can fail so they need replacing. If humans were cloned, their organs could then be used to replace those of sick people. It is currently the case that there are often not enough organ donors around to fulfil this need, so cloning humans would overcome the issue as there would then be a ready supply.

However, for good reasons, many people view this as a worrying development. Firstly, there are religious arguments against it. It would involve creating other human beings and then eventually killing them in order to use their organs, which it could be argued is murder. This is obviously a sin according to religious texts. Also, dilemmas would arise over what rights these people have, as surely they would be humans just like the rest of us. Furthermore, if we have the ability to clone humans, it has to be questioned where this cloning will end. Is it then acceptable for people to start cloning relatives or family members who have died?

To conclude, I do not agree with this procedure due to the ethical issues and dilemmas it would create. Cloning animals has been a positive development, but this is where it should end.

Introduction

The idea of cloning humans for spare body parts is not just the stuff of science fiction—it’s a real, highly debated topic in the world of biotechnology and ethics. With advances in cloning technology, including the successful cloning of animals and progress in stem cell research, it seems increasingly plausible that one day, we might be able to clone human beings for the sole purpose of harvesting their organs or tissues.

But is it ethical? Can we justify the creation of an entire person for the sole purpose of harvesting their body parts? The ethical and moral questions surrounding human cloning are multifaceted, involving not only concerns about individual rights and autonomy but also about the broader implications for society as a whole.

In this article, we will explore the scientific possibilities of cloning humans for spare parts, the moral considerations involved, the potential benefits, and the potential harms. We will also look at the legal and societal frameworks that would need to be put in place to govern such a practice, if it were ever allowed.

The Science Behind Human Cloning

What Is Cloning and How Does It Work?

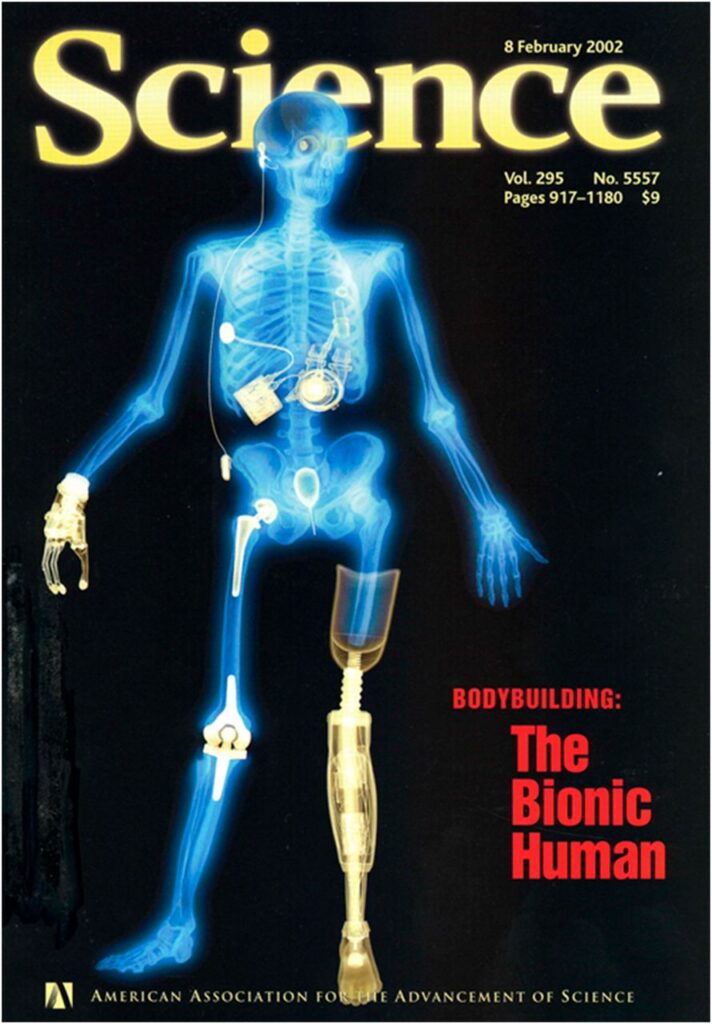

Cloning, in biological terms, refers to the process of creating a genetically identical organism from a single parent organism. There are two main types of cloning: reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning. While reproductive cloning refers to creating a full organism that is genetically identical to the donor (like the famous sheep, Dolly), therapeutic cloning is focused on creating stem cells that are genetically identical to the donor, which can then be used for medical treatments.

Therapeutic cloning, also known as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), has already been used successfully in animals and has the potential for human applications. In this process, the nucleus of an adult cell is inserted into an egg cell, which then starts to divide and develop into an embryo. The cells from this embryo can be harvested for their stem cells, which can potentially grow into different types of tissue or organs.

Cloning for Spare Parts: A Possibility?

The idea of cloning humans specifically for spare body parts, also known as “organ farming” or “organ cloning,” stems from the ability to create genetically identical embryos. These embryos could, in theory, be grown and harvested for organs that match the needs of the original donor, potentially solving the issue of organ shortages that affect millions of people worldwide.

Imagine a world where individuals could create clones of themselves, and in the event of organ failure, transplant organs from their own clones, thus eliminating the risks of organ rejection or the need for long waiting lists for donor organs. While the science is still in its infancy, the potential for medical breakthroughs is enormous.

Ethical Considerations of Cloning for Spare Parts

The Question of Personhood

One of the central ethical issues surrounding cloning for spare parts is the question of personhood. If a clone is created for the purpose of harvesting its organs, does that clone have rights?

Does it deserve the same moral consideration as any other human being?

From a legal and philosophical standpoint, defining personhood is a complex issue. Some argue that a clone, being genetically identical to a human, would have the same rights and moral value as any other person. Others argue that a clone created specifically for harvesting organs could be considered an “artificial” being, whose value is less than that of a naturally born person.

This leads to a moral dilemma: Is it ethical to create a life for the sole purpose of using it as a source of body parts? Even though the clone would technically be a living, sentient being, its very existence would be defined by its ability to serve another’s needs.

The Ethics of Sacrificing One Life for Another

The ethical question of whether it is morally acceptable to sacrifice one life to save another is a key concern in the cloning debate. If cloning humans for spare parts becomes a reality, there would be an inherent power imbalance between the person who owns the clone and the clone itself. The clone’s life would be predetermined to be subservient to the needs of the original person, which could lead to exploitation, abuse, and severe moral consequences.

Moreover, there is the question of whether cloning for organ harvesting would reduce the value of human life itself. If human beings become objects to be exploited for their parts, what does that say about how society views individuals and the sanctity of life? The concept of bodily autonomy, or the right to make decisions about one’s own body, is central to ethical discussions of cloning and organ harvesting.

The Potential for Exploitation and Abuse

If human cloning for spare parts were ever made legal, there would likely be significant risks of exploitation and abuse. Wealthy individuals who could afford to clone themselves might create multiple clones to harvest organs as needed, while those in less privileged positions could be subjected to unethical cloning practices.

In the worst-case scenario, cloning could become a form of modern-day slavery, where clones are created for the sole purpose of serving their “originals.” These clones would have no autonomy, and their entire existence would revolve around the whims and desires of those who created them. The moral implications of such a system are enormous, and it’s difficult to see how it could ever be justified.

Potential Benefits of Cloning for Medical Purposes

Solving the Organ Shortage Crisis

One of the most compelling arguments in favor of cloning for spare parts is the potential to solve the organ shortage crisis. According to the World Health Organization, over 130,000 people around the world are currently waiting for organ transplants, with many dying while on waiting lists. If cloning technology could be perfected to create genetically identical organs, this waiting list could be eliminated.

In theory, cloning could provide a solution to the organ shortage problem by allowing patients to grow organs that perfectly match their bodies, eliminating the risk of rejection that often accompanies organ transplants. Cloning could also provide a means to create organs that are free from disease, potentially reducing the need for long-term medical treatment following a transplant.

Regenerating Damaged Tissue and Organs

Beyond organ transplantation, cloning could also offer the potential to regenerate damaged tissue or organs. For example, if an individual suffers from heart disease or liver failure, cloned cells could be used to regenerate the damaged tissue, improving quality of life without the need for a full organ transplant.

Stem cell research, which is closely linked to therapeutic cloning, has already shown promise in the treatment of various diseases and injuries. In the future, cloning could allow for the creation of personalized therapies that are tailored to the specific genetic makeup of a patient.

Avoiding the Risks of Organ Rejection

One of the most significant challenges of organ transplantation today is the risk of organ rejection. Even with the best immunosuppressive drugs, patients often experience rejection of transplanted organs, which can lead to severe health complications and even death. By creating a clone of the patient, the need for immunosuppressive drugs could be eliminated, as the organ would be genetically identical to the recipient’s original tissue.

This could dramatically improve the success rate of organ transplants and reduce the strain on both patients and healthcare systems. Additionally, it could lead to fewer long-term complications and a better quality of life for transplant recipients.

The Legal and Societal Implications of Cloning for Spare Parts

Legal Frameworks: Who Owns the Clone?

If human cloning for spare parts were to become a reality, legal frameworks would need to be put in place to protect the rights of clones and regulate their creation. The most obvious legal question is: who owns the clone? If someone creates a clone of themselves for the purpose of harvesting organs, does the clone have rights? Can the original person “own” the clone and decide when to harvest its organs?

In many ways, this legal issue mirrors the ethical concerns about personhood. If a clone is created for the express purpose of harvesting organs, does that diminish its legal rights? Alternatively, would clones be granted full personhood under the law, with all the rights and protections that go along with it?

Social Stratification and Inequality

Another societal implication of cloning for spare parts is the potential for increased social stratification and inequality. If only wealthy individuals or nations have access to cloning technology, it could create a situation where the rich have access to life-saving organs while the poor are left behind. This could exacerbate existing inequalities and create a system where access to medical care becomes even more tied to economic status.

Moreover, if clones are created for the sole purpose of organ harvesting, it could lead to further dehumanization and exploitation of vulnerable populations. The question of whether clones would be treated as full individuals or as mere commodities is a critical issue that would need to be addressed.

The Psychological and Societal Impact of Cloning

The Psychological Effects on the Clone

A crucial aspect of the ethical dilemma of cloning for spare body parts revolves around the psychological impact it would have on the clone itself. While cloning technology is primarily focused on creating identical genetic material, there is little understanding of how these clones would develop psychologically. Would a clone, who is genetically identical to another person, experience the same emotions, thoughts, and consciousness as the original person? Or would they develop their own unique personality?

The issue of identity is also a significant concern. A clone could feel a lack of autonomy or develop a sense of existential anxiety, knowing that its creation was for the explicit purpose of serving another person’s needs. The psychological burden of being created for organ harvesting could lead to severe emotional and mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and a lack of self-worth. The clone might be aware that it has no true “purpose” except to serve the needs of another human being, which could result in significant identity crises.

If cloning were ever legalized for medical purposes, such psychological considerations would need to be addressed thoroughly. Would clones be entitled to the same mental health resources as naturally born humans? Would they have the right to live freely without the constant expectation that they would be harvested for their parts?

The Impact on Society’s Moral Compass

On a larger scale, the introduction of human cloning for spare parts would challenge society’s moral framework. Human cloning brings to the forefront difficult questions about the nature of human dignity, the sanctity of life, and the value of individual autonomy.

Cloning for organ harvesting could erode the concept of the inherent value of human life, making it harder for society to uphold the fundamental idea that every human being deserves respect, regardless of their perceived utility. If we start to see clones as nothing more than “organ banks,” it could have ripple effects on how we view human life as a whole. This could dehumanize not just clones, but society’s attitudes toward all human beings, as the distinction between a person and a commodity could become dangerously blurred.

Additionally, cloning could create a class of human beings who are born solely to serve others. This could lead to an era of exploitation that echoes the worst periods of human history, such as slavery or the exploitation of marginalized groups. Society must ask whether such an ethical breach could be justified, even if the health benefits could be significant for some.

Could Clones Ever Be Fully Free?

If humans are cloned for spare parts, there is a significant question about autonomy. Would clones have the ability to make their own choices, or would their lives be controlled by the person who created them? Would they have the right to an education, career, family life, or the ability to pursue their own happiness? Or would they be kept in isolation, used only when needed?

If a clone’s life is reduced to nothing more than that of a “spare part,” there would be significant implications for their mental and emotional well-being. Furthermore, we must also consider whether society would allow clones to integrate fully into normal social life. Would they be segregated, ostracized, or treated as second-class citizens due to their origins?

Regulating Human Cloning: The Path Forward

Establishing Legal Protections and Rights for Clones

Given the ethical, psychological, and societal challenges posed by cloning for spare parts, it is clear that any future regulation of human cloning would require careful consideration of clones’ rights. Laws would need to be created to protect clones from exploitation and abuse. These protections would need to ensure that clones are treated as individuals with autonomy, rather than as mere sources of body parts.For instance, the law could treat clones as full legal persons with the same rights as any other human being. This could include the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as well as protections from involuntary organ harvesting. It would be crucial to establish guidelines on how clones could be created and used, including clear regulations on informed consent, autonomy, and the ethical treatment of clones.

Moreover, the legal system would need to set clear rules regarding the ownership and control of a clone. Would the creator of the clone own the clone? Or would the clone, as a unique person, have legal and human rights that supersede the rights of the original? Such questions would need to be settled to prevent the abuse of cloning technology.

International Cooperation and Regulation

Given the profound ethical questions surrounding cloning, any global effort to regulate the practice would require international cooperation. If one country or region were to legalize cloning for spare parts, it could create a ripple effect, influencing other regions to follow suit—or to ban the practice outright.

International conventions or treaties might be necessary to ensure a consistent ethical approach to cloning. These agreements could regulate the creation and use of clones, ensuring that their rights are respected worldwide. Countries might agree on a universal framework to protect clones from exploitation, similar to human rights treaties, which could prevent the development of a “cloning industry” in less regulated regions.

Moreover, the practice of cloning for spare parts could raise significant concerns related to human trafficking, black markets, and unethical practices. It would be crucial for global authorities to ensure that cloning is not exploited for profit or to undermine human rights.

The Long-Term Impact of Cloning on Human Evolution

The Risk of Genetic Homogenization

One of the broader concerns about cloning technology, whether for spare parts or reproductive purposes, is the potential impact on human genetic diversity. If humans began to clone themselves as a common practice—particularly for the purpose of organ harvesting—it could lead to a decrease in genetic diversity.

Genetic diversity is crucial for the survival and adaptability of any species. A lack of genetic diversity could lead to an increased susceptibility to disease, environmental changes, and other challenges that might threaten human existence. While clones would not be exact copies in terms of their environmental experiences, the reduction in genetic variety could have unforeseen negative consequences for human evolution.

The Potential for Genetic Engineering and Designer Babies

As cloning technology improves, it may become increasingly linked to genetic engineering. In the future, cloning could be combined with gene editing techniques like CRISPR, which allow for precise modifications to an organism’s DNA. While this could potentially improve the quality of life for individuals—by creating clones without genetic diseases or by enhancing certain physical attributes—it could also open the door to a form of genetic elitism.

If cloning were to become a common practice, society could face a future in which individuals are engineered for specific traits, including physical attributes, intelligence, and health. This could lead to a new form of social stratification, where those who can afford genetic modifications or cloning would have a significant advantage over those who cannot. It could create a society in which the rich have access to superior genetics, while the poor are left behind.

Conclusion

The question of whether it would be ethical to clone humans for spare body parts presents a complex and multifaceted dilemma. While the scientific advancements in cloning and stem cell research offer the tantalizing possibility of solving the global organ shortage crisis, the ethical implications are vast and deeply concerning. Creating human clones specifically for harvesting organs raises significant questions about the nature of personhood, autonomy, and human rights. Can a cloned individual truly be treated as a person if their existence is defined by their role as a biological resource? And should society accept the dehumanization of a living being for the sake of medical convenience?

While the potential medical benefits of cloning for organ harvesting—such as eliminating organ rejection and providing a continuous supply of compatible organs—cannot be ignored, the moral cost may be too high. The risks of exploitation, abuse, and the psychological toll on the clone would be immense, creating a scenario where the value of human life itself could be diminished. The societal and legal frameworks needed to regulate human cloning would need to be robust, protecting clones’ rights and ensuring that they are not treated as mere tools for others’ benefit.

Ultimately, as a society, we must tread carefully when contemplating such profound technological advancements. The ethical balance between medical progress and the inherent dignity of human life is a delicate one, and any decision to pursue human cloning must be guided by respect for the autonomy, rights, and value of all human beings—whether naturally born or artificially created.

Q&A

Q: Why is cloning for spare parts considered unethical by many?

A: Cloning for spare parts is considered unethical due to the moral implications of creating a human being solely for the purpose of harvesting their organs, which raises concerns about personhood, exploitation, and autonomy.

Q: Could cloning for organs help solve the global organ shortage?

A: Yes, cloning could potentially solve the organ shortage by providing a renewable, genetically identical source of organs, eliminating the risks of organ rejection and long transplant waiting lists.

Q: What would be the psychological impact on a cloned individual?

A: A cloned individual could experience psychological distress due to the knowledge that their existence is primarily for organ harvesting, potentially leading to issues such as anxiety, depression, and a lack of self-worth.

Q: How would the legal system address the rights of clones?

A: The legal system would need to establish clear frameworks to protect the rights of clones, ensuring they are treated as individuals with autonomy, not just as biological resources for organ harvesting.

Q: Would cloning for organs lead to societal exploitation?

A: Yes, cloning could lead to exploitation, especially in a world where wealthier individuals or countries may create clones for organ harvesting, exacerbating inequality and potentially reducing the value of human life.

Q: Could clones be integrated into society fully?

A: While theoretically possible, it’s likely that clones created for organ harvesting would face significant challenges integrating into society, as they might be seen as second-class citizens or face discrimination due to their origins.

Q: Would cloning lead to the loss of genetic diversity?

A: Yes, widespread cloning could result in decreased genetic diversity, which is vital for human survival and adaptability. This reduction could increase susceptibility to diseases and environmental changes.

Q: Could cloning be used for other medical purposes aside from organ harvesting?

A: Yes, cloning could be used to regenerate damaged tissues or organs, as well as potentially for personalized stem cell therapies, offering a way to treat various diseases without the need for full organ transplants.

Q: What role would international regulation play in cloning for spare parts?

A: International regulation would be crucial to ensure that cloning is done ethically, preventing exploitation, abuse, and the creation of a global market for human clones. Such regulation would aim to protect clones’ rights universally.

Q: Could cloning for spare parts lead to genetic engineering and designer babies?

A: Yes, cloning combined with genetic engineering could create the possibility of designing babies with specific traits, which could lead to genetic elitism and exacerbate social inequality, further complicating the ethical landscape.